The need for continuous baseload power has been a recurring theme for years, with coal and gas seen as firming options. Nuclear power has also been considered as a non-carbon emitting alternative and given that Australia does not have a commercial nuclear industry, the concept of ‘off the shelf’ nuclear small modular reactors (SMRs) has been raised, particularly by the Coalition. But is this a reasonable response to Australia’s need to transition rapidly to a low carbon future?

There are a number of layers to this question. Apart from increasing needs for non-polluting power, Peter Dutton recently suggested that Australia should not be dependent on China as a major source of solar and wind technology but should instead overturn its legislative ban on nuclear power, and supplement that technology by introducing nuclear SMRs or Micro Modular Reactors (MMRs) from the US, UK, France “and other trusted partners”. By calling SMRs a ‘companion technology to renewables’, he was clearly trying to tread a line between Coalition hardliners and Teal voters opposed to high carbon emissions. He went on to say that “there is no better example of the risk of over-reliance on one market than what we saw with many European countries’ dependence on Russian gas”, and that the nuclear submarines Australia is committed to under AUKUS “are essentially floating SMRs”.

An important economic marketing point was that the inclusion of nuclear would facilitate the pathway to “an Australia where we can decarbonise and, at the same time, deliver cheaper, more reliable and lower emission electricity”. By comparison, a report by the Australian Conservation Foundation in October 2023 said the next generation of nuclear reactors being advocated by the Coalition would ‘raise electricity prices, slow the uptake of renewables and introduce new risks from nuclear waste’.

If you have an instinctive response to the nuclear option (either negative or positive) but need evidence to confirm or reject your assumptions and question your certainties, so do I. France’s dependence on nuclear power, Sweden’s continued use of nuclear energy despite an earlier referendum to close it down and Germany’s concerns for the complete closure of nuclear power in 2023 are lessons to be considered.

So that’s where ‘The Drill’ comes in …..

Can the answers be found in a few hours of online enquiry, using the scientific method and unbiased evidence – although unbiased evidence is clearly an oxymoron.

In this edition of ‘The Drill’, I plan to frame the question, provide methods for the search, succinct results without commentary and a short more discursive discussion. Then you make your own conclusions, including responding if you can identify where I may have gone wrong!

Aims: There are many nuclear questions but I’m restricting this to: are nuclear small modular reactors (SMRs) being used successfully elsewhere, and if so, do they have a future in Australia’s energy transition and mix?

Methods: I searched for information relating to this question in publicly accessible reports from 2022-2024. This proved to be more challenging than expected, because in most cases, reports were published by stakeholders with conflicts of interest. The most balanced report was luckily the most comprehensive from the CSIRO. The web URLs for my sources are provided below.

Results:

First, we do need some definitions.

Nuclear SMRs are newer generation reactors defined by their power output. They are designed to generate electric power at typically less than 300 Mwelectric (MWe) and may also be used for non-electrical industrial applications such as water desalination and heat generation for industry. According to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Booklet on Advances in SMR Technology Developments published in 2022, there are more than 80 SMR concepts currently under development, ranging from single-unit installations to multimodule plants. Manufacturing, assembly and testing may occur in factory, and siting may be on ground, underground, floating, underwater or movable. Therefore, nuclear SMRs may be applicable to regions lacking electrical grid and cooling water infrastructure.

Where are nuclear SMRs currently operating?

China has one prototype nuclear SMR, the Linglong-1, which is a multi-purpose 125 Mwe pressurised water reactor. Construction started on 13 July 2021 and according to Chinese Global Times (6 September 2023) it is expected to be completed and put into operation in 2026. China sees potential for deploying nuclear SMR technology and Chinese professionals to oversee it to partner countries, particularly developing countries and those participating in the Belt and Road initiative. A spokesperson for the Nuclear Power Institute of China said that The Linglong-1 is a highly suitable nuclear energy technology for cities that have a relatively small grid, and for islands where large nuclear plants cannot fit.

A 2023 report Ordered by the British House of Commons (13 July 2023) highlighted the investment by China in the UK energy market and in particular in the nuclear energy sector, and seeks to further its influence by exporting nuclear technology.

Russia has four land-based operating EGP-6 SMRs, which form the Bilibino Nuclear Power Plant, commissioned in 1974-1977. The reactors supply Bilibino with a population of around 5000 people (many of whom are employed by the plant), with electricity, heated water, and steam. The EGP-6 (the acronym standing for Power Heterogenous Loop reactor) are SMRs that are scaled down versions of the larger RBMK design. Both use water for cooling and graphite as a neutron moderator, and the EGP-6 reactors are the only reactors to be built on perma-frost. As of 2020, the power plant was ready for decommissioning, to be replaced by the Akademik Lomonosov floating nuclear power plant, The first EGP-6 reactor was shut down in December 2018, and the other three EGP-6 reactors were scheduled to follow in December 2021, however a decision was made in 2020 to renew the license of one of the three reactors until December 2025.

Russia has a number of nuclear SMRs in design and development stages including the BREST reactor, a lead-cooled fast reactor, the main characteristics of which are passive safety and a closed fuel cycle. Lead is chosen as a coolant for being high-boiling, radiation-resistant, low-activated and at atmospheric pressure. Russia on Wikipedia here and here

In the USA the only commercial SMR project to receive design certification from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (an essential step before construction can commence), was cancelled in November 2023. The Utah Associated Municipal Power Systems project (UAMPS) was the developer of a nuclear SMR project called the Carbon Free Power Project, with a gross capacity of 462MW and planned to be fully operational by 2030. In late 2022 UAMPS updated their capital cost to $31,100/kW citing the global inflationary pressures that have increased the cost of all electricity generation. The CSIRO Gencost report states that ‘This estimate implies that nuclear SMRs have been hit by a 70% cost increase, which is much larger than the average 20% observed in other technologies. The significant increase in costs likely explains the cancellation of the project.’ This was the only proposed SMR in the USA with regulatory approval.

What is the cost of electricity production using nuclear SMRs?

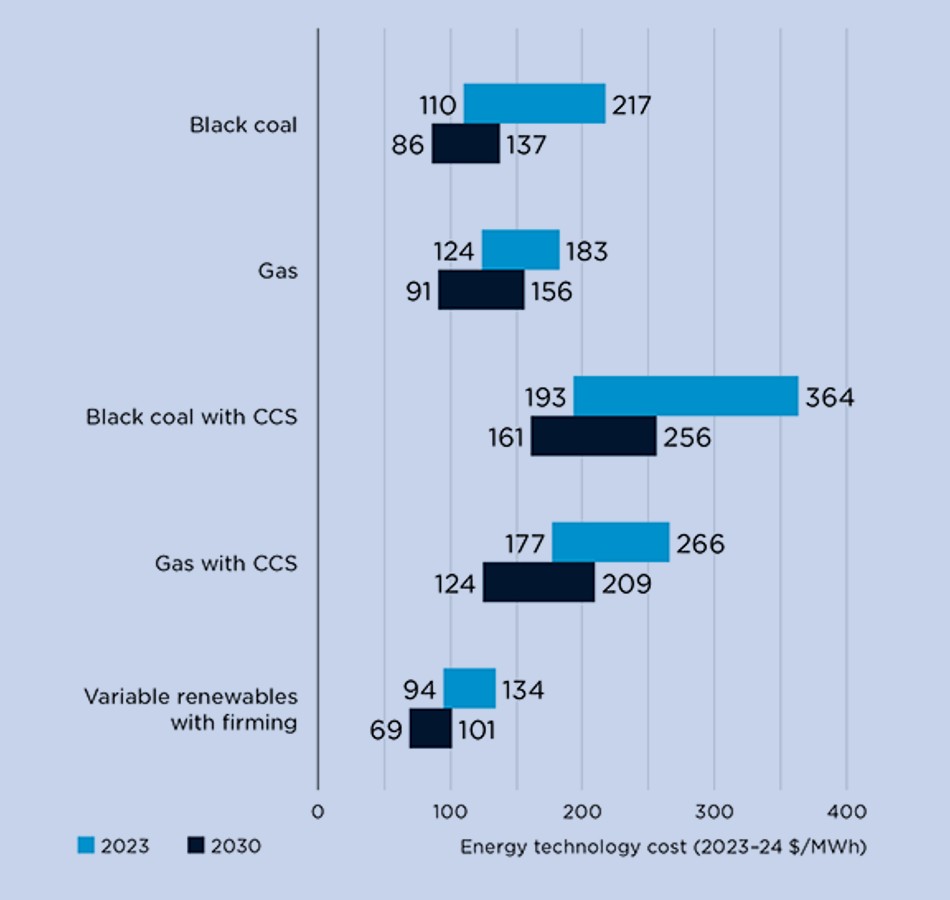

Each year the CSIRO and the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) work with industry and key stakeholders to produce cost estimates for new-build electricity generation in Australia (Gencost). This is Australia’s most comprehensive electricity generation cost projection report. The 2023-2024 draft Gencost report was recently released. It utilises the ‘levelised cost of electricity’ (LCOE) cost comparison metric, being ‘the total unit cost a generator must recover to meet all its costs, including a return on investment’. High and low-cost estimates are used to produce an LCOE range for each technologyGencost stated that ‘The LCOE cost range for variable renewables [wind and solar power] with integration costs is the lowest of all new-build technologies in 2023 and is predicted to be lowest in 2030. The cost range overlaps slightly with the lower end of the cost range for coal and gas generation, but those costs are only achievable if they can deliver a high capacity, source low-cost fuel and be financed at a rate that does not include climate policy risk, despite their high emissions, which is a non-viable option. If we exclude high emission generation options (coal and gas), the next most competitive generation technology is gas with carbon capture and storage’ (see graph below).

For nuclear SMRs, Gencost stated that conflicting data has been published. Projects completed or in construction in Russia and China are 100% government funded and as indicated above, the Utah Associated Municipal Power Systems project was cancelled in November 2023 due to cost over runs.

Costs for all technologies increased in 2022-2023. The cost increase for large scale solar was the lowest at 9%, and this increase was expected to be reversed in 2023-2024, with a cost decline of 8% predicted. Onshore wind saw significant increases in costs in 2022 – 2023 of 35%, with a further increase of 8% expected in 2023-2024. According to the CSIRO, cost pressures were likely to remain for new-build gas, onshore wind and nuclear SMRs.

- CSIRO draft 2023-2024 Gencost report

- International Atomic Energy Agency reports

- Wikipedia

- In a House of Commons Security Committee China report (printed 13 July 2023)

- The Global Times

- World Nuclear News

- https://world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Linglong-One-reactor-pit-installed-at-Changjiang

- https://world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Six-SMR-power-plants-approved-in-Poland

- https://world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Palisades-SMR-programme-is-under-way-Holtec

- Power Digest

- World Nuclear Organisation

- CNBC and the Guardian here and here

- Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences May 31, 2022 119 (23) e2111833119

- Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies

- Reuters